Tax‑Aware Long-Short Investing, Explained

Introduction

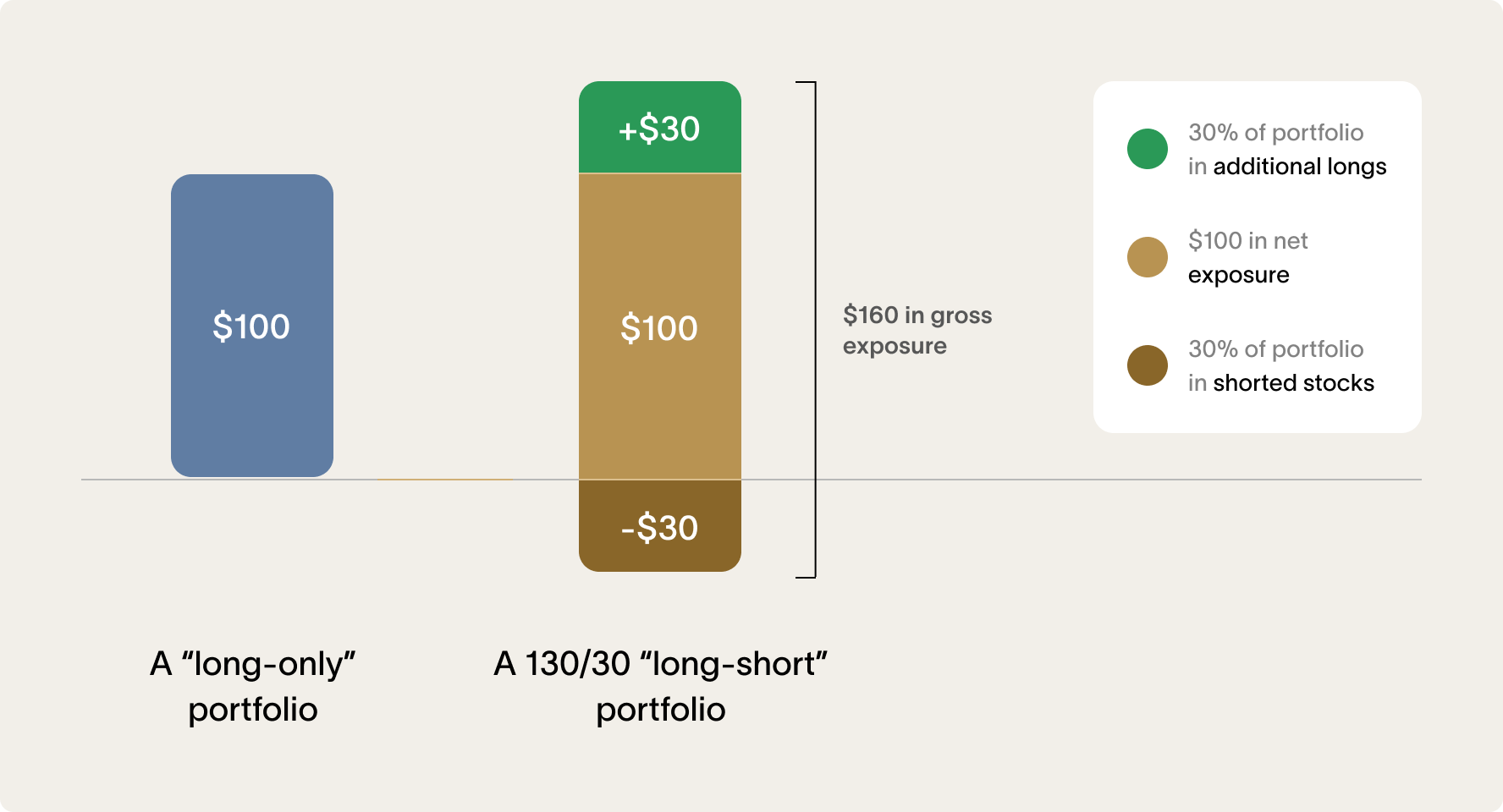

A tax-aware long-short strategy (also called “long-short direct indexing”, "long-short loss-harvesting strategy", or “130/30”) is a way to magnify tax-loss harvesting. Margin borrowing and short sales are used to put additional dollars to work with loss-generating expectations, while the overall portfolio continues to track a broad market index. Realized capital losses can offset capital gains elsewhere in the portfolio.

In simple terms, a long-short manager borrows against your portfolio and invests more in the market. A nearly equal dollar amount is sold short (a bet against the market) so that your overall market exposure stays at 100%.

In a 130/30 setup, an investor deposits $100 of cash and stocks into the account. The manager borrows $30 to buy more stocks (the “long” leg). Another $30 of stocks is borrowed and sold to the market (the “short” leg), with the cash proceeds held in escrow. Net exposure is still $100 ($100 + $30 − $30), but gross exposure rises to $160. The extra $60 is used to enhance tax-loss harvesting without changing the investment objective.

Executed properly, this structure is designed to counterbalance the added risks of leverage while generating additional tax losses, ideally even in calm or rising markets.

Research shows that tax-aware long-short can generate significantly higher tax losses than traditional direct indexing. Investors, however, need to understand the higher risk from leverage, the difficulty of managing shorts well, and the eventual tax realization required when moving from a long-short portfolio back to a long-only or un-leveraged one.

The Problem: “Portfolio Lock‑In” with Direct Indexing

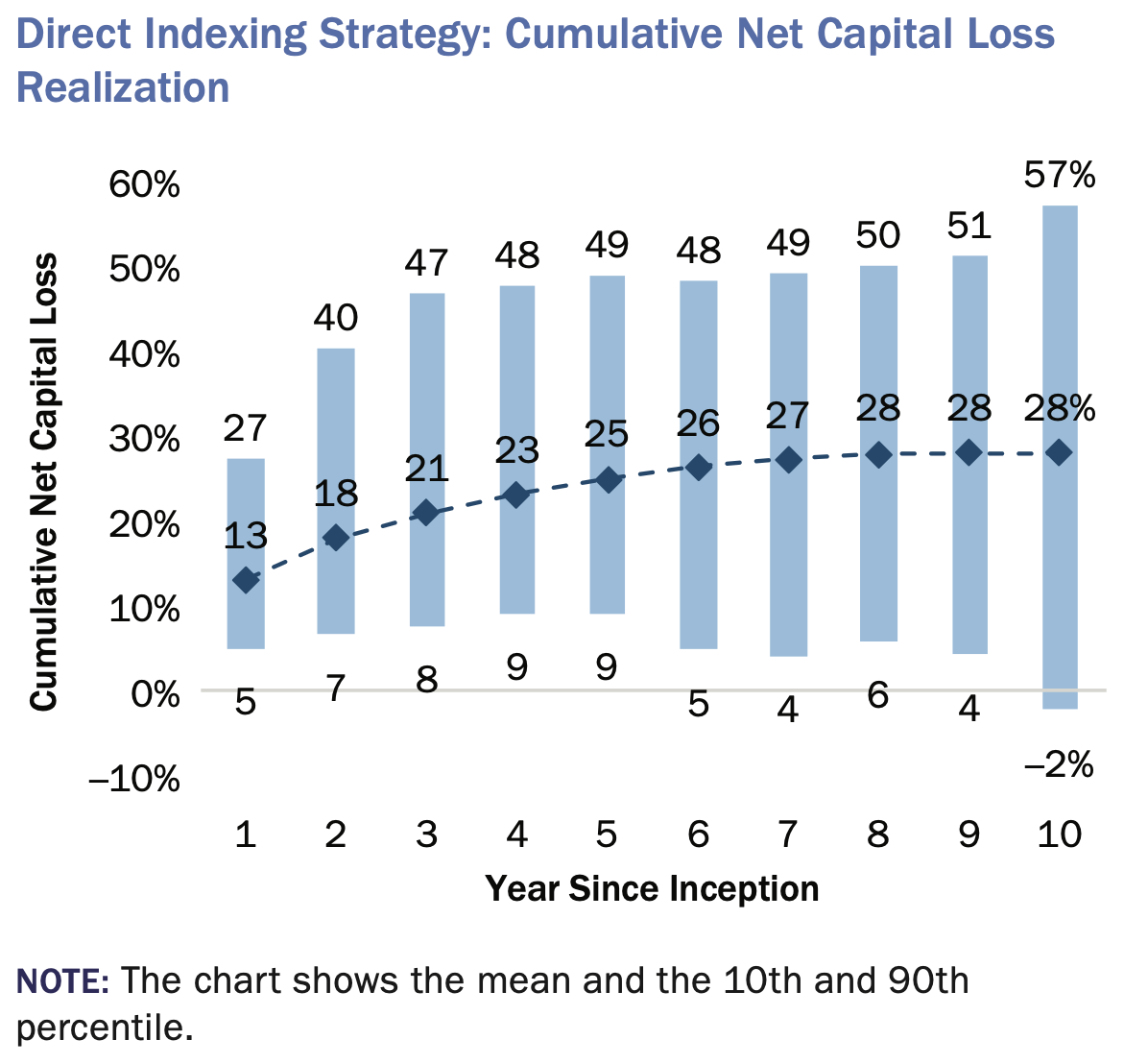

Over long horizons, markets tend to rise. In a standard direct indexing account, this means harvestable losses gradually shrink. After the first few years, most positions sit at a net gain, so realized losses decline and eventually level off.

In large-sample simulations, cumulative net realized losses for long-only direct indexing climb early and then flatten near roughly 30% of initial capital. Year-one loss rates are the highest, then they fall steadily until the portfolio becomes “locked in” or “ossified.”

At that point, the direct indexing engine is doing very little for you. You are still paying (usually higher) fees, but one of the core benefits, a reliable stream of losses, has likely faded.

How the Long-Short Overcomes "Lock-in"

A tax-aware long-short overlay refreshes your portfolio’s loss-generating capacity without changing your net market exposure. Using your portfolio as collateral, the manager borrows money, invests in the market, and offsets that with short positions, often of a similar size. Net exposure in most models stays near 100%, while gross exposure scales with your risk appetite.

With more dollars at work, the extra-long exposure creates more opportunities to harvest losses, but it is often the short exposure that is tuned to act as a loss generator. Shorts are expected to lose value over time because they bet against a market that, over the long term, generally rises. This design lets you harvest losses in most environments, whether in a bull market where stocks are rising or a bear market where they are falling.

You may see ratios like 130/30, 160/60, or 250/150. Net exposure is the difference between the two numbers. Gross exposure, the dollars working for you, is the sum. Leverage ratio is gross exposure divided by net exposure. A 130/30 portfolio has a 1.6x leverage ratio; a 250/150 portfolio has a much higher ratio.

This setup helps overcome the lock-in effect of direct indexing. With sensible leverage and tracking-error controls, cumulative net losses can remain persistent and much larger, and some providers report generating losses equal to 100% of the initial capital within a few years.

A simple analogy: think of a well-structured fitness program. You build muscle with targeted training (the extra long exposure) and shed fat with disciplined nutrition (the short book). Your overall weight stays similar, but the total activity helps you reach your goals, as long as the program is well designed.

How it works, step‑by‑step

- Fund the brokerage account. Deposit stocks, index funds, or cash. Assume $1 million for this example.

- Borrow on portfolio margin. The manager uses your $1 million as collateral to borrow $300,000 (for a 130/30 structure that is 30% of the account).

- Buy long and sell short. The manager buys a diversified basket of stocks for $300,000 and sells short an equal amount, keeping net market exposure near the original $1 million, with gross exposure of about $1.6 million.

- Continuously harvest. In rising markets, shorts lose value. In falling markets, longs lose value. Individual stocks that move differently from the market may also create losses. When specific lots fall below their purchase price, the manager realizes the loss and swaps into similar but not “substantially identical” stocks to maintain exposure while following IRS wash-sale rules.

- Rinse and repeat. New lots are created regularly on both sides, keeping the pool of harvestable losses replenished.

Where the Tax Value Comes From

- Volatility and dispersion: Even in strong years, many stocks are down at any point in time. The long-short overlay increases the number of stocks and dollars that pass through loss-harvest screens.

- Fresh basis: New long and short trades create new purchase prices. More fresh lots mean more chances to harvest as prices move.

- Term management: Skilled managers try to realize losses and defer gains, and to tilt any realized gains toward long-term treatment when possible.

- Persistence: Because new lots are constantly created, loss capacity does not deteriorate after two to three years. This directly addresses the lock-in problem seen in long-only direct indexing.

What the Tax Code Cares About

- Economic Substance

The tax code disallows transactions undertaken solely for tax benefits, without an economic substance. In this strategy, additional longs and shorts could be questioned if they exist only to generate losses. A robust program has meaningful pre-tax objectives. A “long-short direct indexing” provider that promises very low tracking error relative to the benchmark may invite scrutiny about economic substance. - Wash‑Sale Rule (the 30‑day window)

If you sell a security at a loss and buy the same or a “substantially identical” security 30 days before or after, the loss is disallowed and added to the basis of the replacement shares. Managers avoid this by using close substitutes rather than identical securities and by coordinating across household accounts. IRS Publication 550 gives examples and guidance. Some investments that track the same index can be considered “substantially identical” in practice. - Constructive Sales

If you own a low-basis stock in any account and short the same stock, the IRS may treat it as if you sold the stock and you may owe capital gains immediately. A disciplined manager avoids “shorting against the box” across the whole household.

- Short‑Sale and Margin Tax Items

When you short a dividend-paying stock, you compensate the lender for the dividend. These substitute payments are generally not dividends to you and may be treated as ordinary income to the recipient. Your ability to deduct them follows specific timing tests (for example, short held at least 46 days to deduct as investment interest).

Interest paid to borrow for investments is usually investment interest expense. It is deductible up to your net investment income, and any unused amount can carry forward.

Costs and Frictions to Consider

Tax-aware long-short strategies involve several costs and frictions:

- Management and trading costs. You pay a manager to run a complex Separately Managed Account (SMA) with regular trading, compliance, and reporting.

- Financing costs. Margin interest on the borrowed “extra” longs, usually a spread over short-term rates. Institutional managers may negotiate tighter spreads. Rebates from shorts can offset part of this cost.

- Stock-borrow fees. Fees on the short side vary by security and by supply and demand in the lending market. “Hard-to-borrow” names can be expensive or temporarily unavailable.

- Dividend economics on shorts. If a shorted company pays a dividend, you owe a payment in lieu to the lender. These payments differ from ordinary dividends and you should expect cash drawn from your portfolio for them.

- Exit costs. Once you have harvested substantial losses, you may want to reduce leverage and risk. Exiting a long-short strategy requires careful planning over multiple years and will eventually lead to realizing a meaningful capital gain.

An experienced manager will try to optimize cost efficiency by capping borrow-fee exposure, avoiding perennially expensive shorts, staggering lot creation to maximize dispersion, and modeling after-tax outcomes net of financing.

Risks You Need to Understand Carefully

- Pre-tax underperformance risk. By their nature long-short strategy are typically an active strategy. Active stock selection creates tracking errors that can underperform the market. Many long-short approaches use factor tilts or style biases that can shift portfolio behavior over time.

- Leverage and shorting risk. Borrowing against your portfolio exposes you to margin calls if collateral falls. Shorts expose you to potentially large losses if a stock keeps rising. Short squeezes can create rapid losses.

- Wash-sale mistakes. Buying back too soon or choosing a “substantially identical” replacement can disallow a loss and shift basis instead.

- Constructive sale risk. Shorting a stock you already own with a large embedded gain, even in another account, can trigger current-year taxation. Household-level controls are essential.

- Exit risk. Unwinding the overlay forces you to realize deferred gains. Research suggests you can often de-risk gradually over several years and keep much of the benefit, but a full return to unlevered long-only usually recognizes meaningful gains. You will need liquidity elsewhere.

- Manager risk. The strategy is complex and nuanced. Choosing an experienced manager with a sound, documented process is critical.

- Tax-law risk. The approach depends on current rules for loss harvesting and the use of leverage. The economic substance doctrine can challenge a program that mainly targets additional losses through leverage.

When You May Want to Consider This Strategy

A tax-aware long-short SMA is particularly powerful around major financial events, when you need losses to offset gains and manage transitions. Potential use cases include:

- Revitalizing an existing direct indexing portfolio that has few losses left.

- Preparing for a company sale or other large liquidity event.

- Offsetting gains from the sale of appreciated real estate.

- Managing tax exposure when repositioning inherited assets with low basis.

- Diversifying a concentrated stock position while hedging risk during the transition.

- Pre-IPO planning to build up realized losses before an IPO unlock.

How Much of Your Portfolio Should You Allocate?

One way to think about this is to use a simple framing: your “loss demand” versus the strategy’s “loss capacity.”

- Estimate your loss demand.

Add realized capital gains this year to gains you expect over the next one to three years. That is the total loss you can actually use. - Pick an intensity that matches demand and risk comfort.

While you should consider your own risk tolerance and work with an Advisor if you need help below are some potential options

- Less Leverage. Allocate 5–10% of taxable equities to a 130/30 program. You are learning the mechanics and covering part of expected gains.

- Moderate. Allocate 10–20% to a 130/30 or 150/50 program if gains are steady and you accept some factor and leverage exposure.

- Aggressive. Allocate 20–30% or more with higher extensions (for example 150/50 or above) if you expect large, recurring gains and can tolerate more complexity and risk.

- Calibrate with ranges, not point estimates.

Ask your manager for historical ranges of realized losses by leverage level and benchmark, net of financing and borrow fees. Peer-reviewed research shows clear advantages for long-short versus direct indexing, but outcomes vary. Size the allocation toward the middle of the range that matches your demand, then adjust using real results from your first six to twelve months.

A tax-aware long-short SMA can be funded with many liquid, marketable assets, including publicly traded stocks, ETFs, mutual funds, fixed income, and cash.

In most situations, private company stock, unvested RSUs, unexercised options, and highly illiquid positions are not eligible.

If a large share of your wealth is in a single low-basis stock, coordinate the long-short overlay with a plan for that position, such as an exchange fund, charitable gifts, or staged sales. Avoid constructive-sale conflicts.

The Exit (Plan This on Day One)

At some point, you may want less complexity or less financing exposure. A full unwind back to a pure long-only portfolio will generally recognize meaningful gains, so you'll need to plan ahead. An orderly glide path can reduce leverage and tracking error over several years, preserving the gleaned benefits while avoiding a single large gain realization.

Takeaways

If your portfolio is generating substantial capital gains, whether from selling a concentrated position, secondary sales of private stock, partnership distributions, real estate sales, or a future liquidity event, a tax-aware long-short SMA can be a powerful tool to alleviate tax liabilities. The strength of the strategy lies in replenishing “loss inventory” year after year.

Done well, it is a disciplined, rules-driven overlay that trades complexity for a clearer tax picture. Done poorly, it is an unnecessary cost and compliance risk that can drag on performance.

For sophisticated but time-constrained investors, it is worth starting in a measured way, insisting on institutional-quality processes around wash-sales and constructive sales, requiring transparent after-tax reporting, and sizing the allocation to your actual gain stream, not to marketing claims.

Sources

This article is for education only, not tax, legal, or investment advice. Results vary depending on the market, tax status, and implementation details. Consult your tax advisor and read the manager’s documents carefully.

- 26 U.S. Code §1259, Constructive sales treatment for appreciated positions.

- Liberman, Krasner, Sosner, Freitas (AQR), Beyond Direct Indexing: Dynamic Direct Long‑Short Investing, Journal of Beta Investment Strategies, 2023 (cumulative loss capacity, de‑risking mechanics).

- Sosner, N., Krasner, S., & Pyne, T. (2019). The Tax Benefits of Relaxing the Long‑Only Constraint: Do They Come from Character or Deferral? The Journal of Wealth Management,

- Interactive Brokers, Short Sale Cost and Risks of Shorting (borrow‑fee mechanics; variability with supply/demand).

- Morningstar, Wash Sale Challenge: What Is Substantially Identical? (practical interpretation).

--